A Night of Fire

Another's Mystical Experience is Never Meant to Cast Judgment on Our Own.

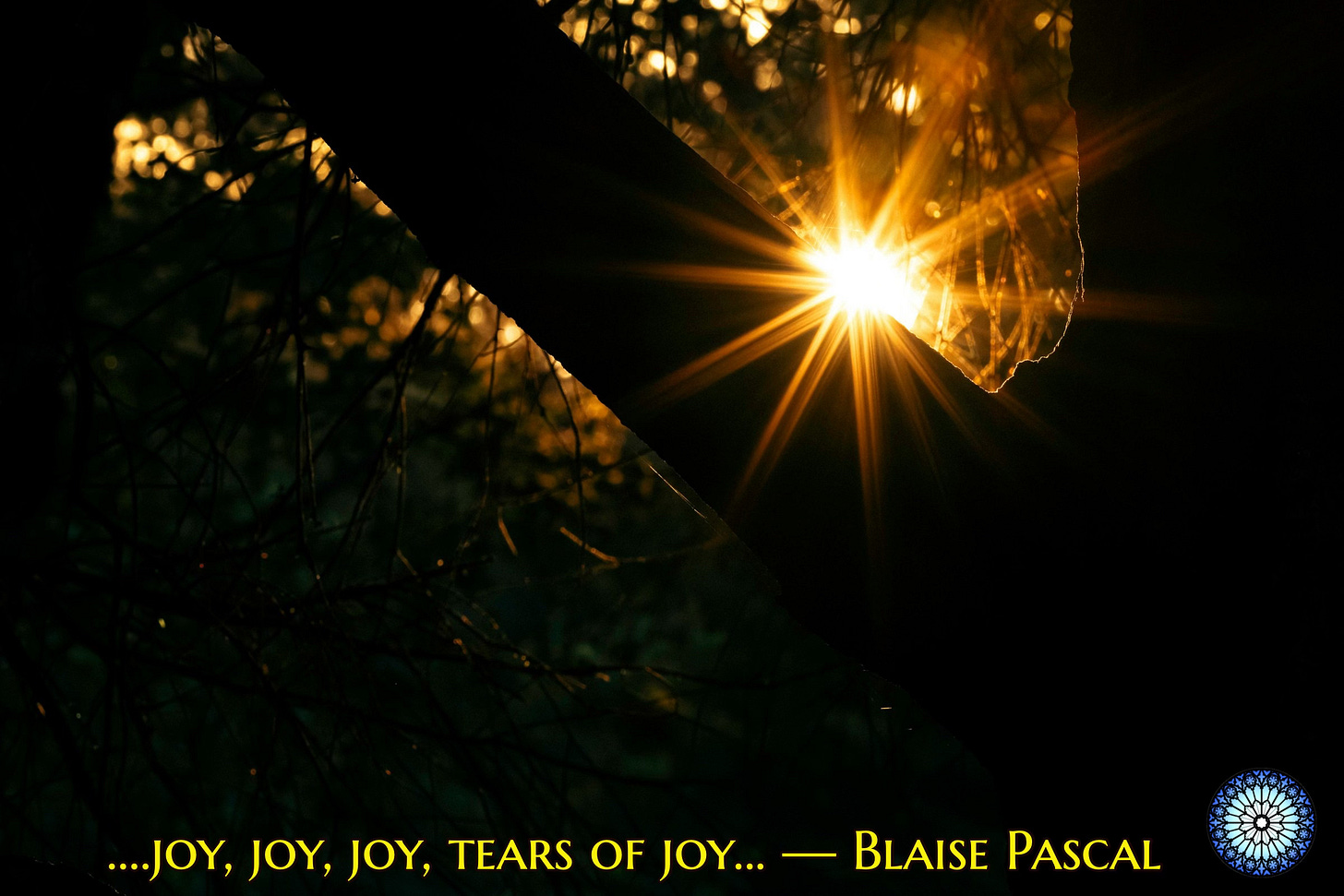

On a Monday night in November of 1654, the French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal experienced a remarkable spiritual encounter. He was alone, and the only record he left of the evening was a cryptic document sewn into his jacket — it was discovered after his death.

Scholars have referred to this as his “night of fire.” In a poetic document t…