Is the Dream Over?

Perhaps when one dream dies, another one simply arises.

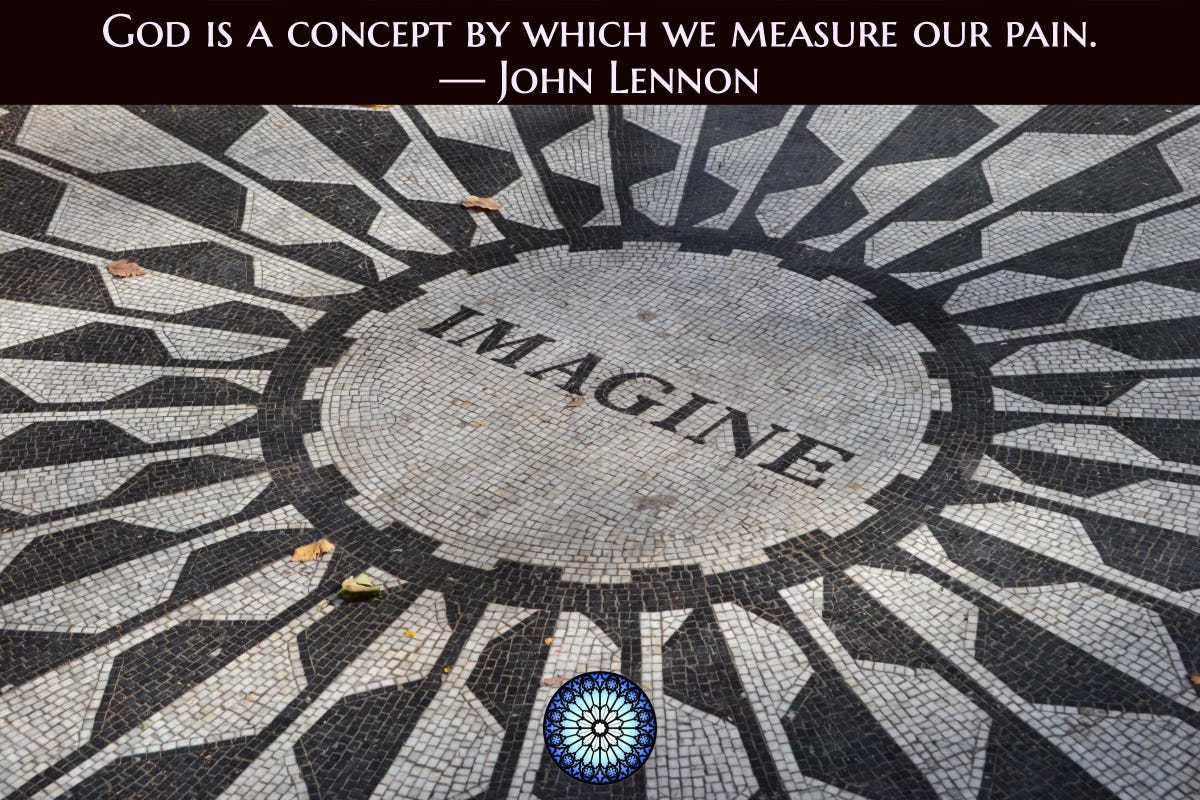

“God is a concept by which we measure our pain.” — John Lennon

It was my college girlfriend’s 20th birthday; we had left campus to grab dinner to celebrate, and on our way back stopped by the local record shop to grab a copy of Yesshows, the latest album by one of my favorite bands. Back at my girlfriend’s room, the phone rang and it was her mom calling …