The Monks Who Couldn't Quarrel

Living in Non-attachment Makes Some Things Impossible.

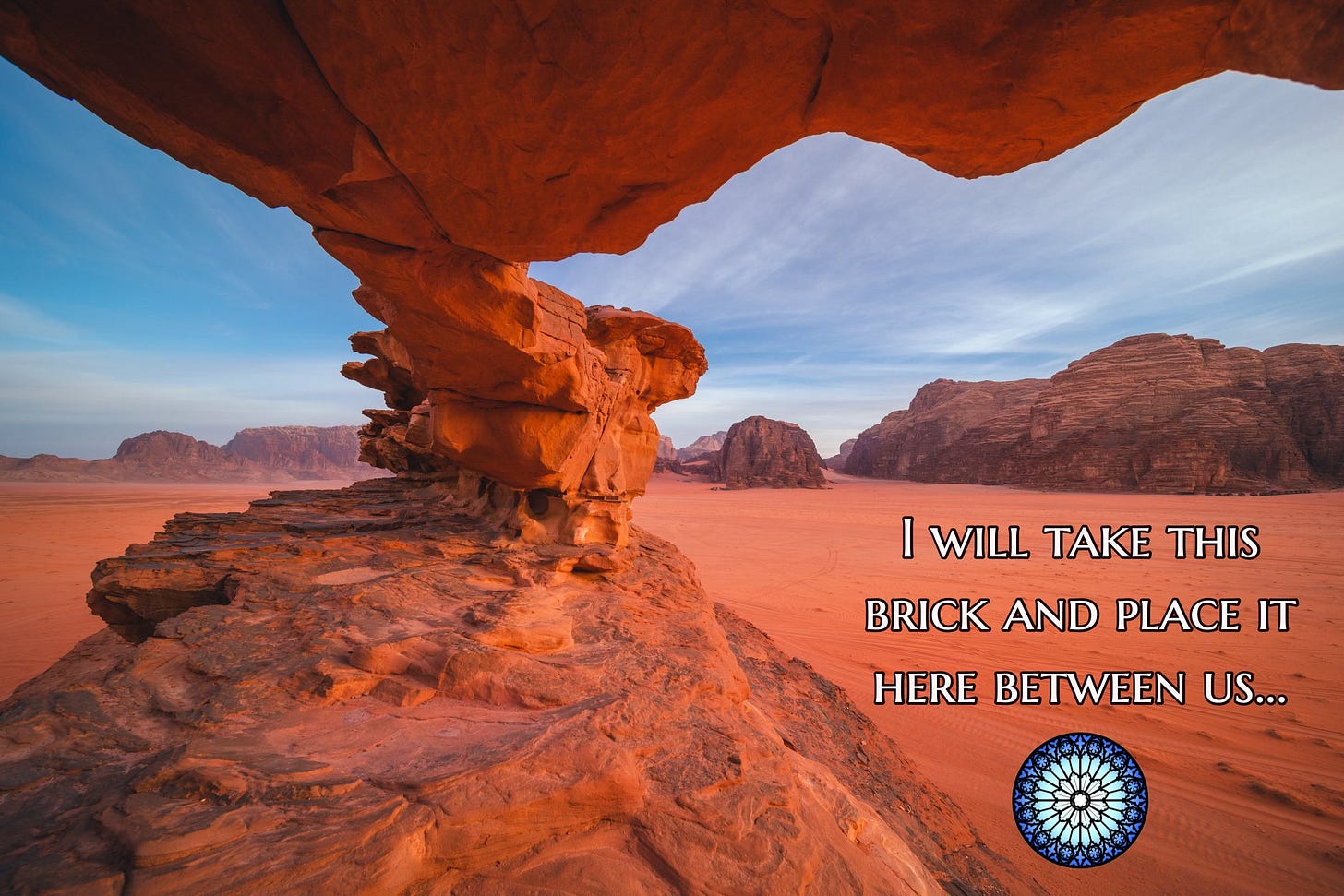

There were two elders living together in a cell, and they had never had so much as one quarrel with one another. One therefore said to the other: Come on, let us have at least one quarrel, like other men. The other said: I don’t know how to start a quarrel. The first said: I will take this brick and place it here between us. Then I will say: It is mine.…